The flying reptiles, pterosaurs, were an amazing successful group of prehistoric animals. They ranged from the Late Triassic through the end of the Cretaceous periods, a span of time of about 156 million years. That is over 2 times longer than the time since dinosaurs became extinct, and mammals have dominated the terrestrial landscape.

Pterosaurs were the first vertebrates to achieve powered flight, followed later by the birds and bats. However, during their hay-day, pterosaurs achieved an incredible range of diversity in form and size, and occupied countless niches within the Mesozoic world.

Interestingly enough, the first pterosaur remains to come from North America were found in Kansas. Flying reptiles had been known from Europe, but during an 1870 collecting trip through the western territories, O. C. Marsh stopped off in Kansas. Near the end of the trip he spotted a long, slender bone weathering out of the chalk formation, and collected what he could before heading back to Yale on the train. He thought the bone looked like the finger bone of the pterodactyls from Europe, but this bone was much larger. He estimated the wing-span to be 20 feet. The next year, he traveled back to collect the rest of the animal in the Kansas formation, and found that in fact his estimate of its giant size was correct. He named this new animal Pteranodon.

Greg dusts the life-sized models of Pteranodon sternbergii in the Sternberg Museum of Natural History

As more and more flying reptiles have been found in the fossil record, as basic question about them has puzzled scientists—how well could they fly? Estimating the body mass is a fundamental part of this inquiry. We can look at modern birds and see the constraints that flight dictates for body mass at least today. How do the pterosaurs compare?

In a recent publication, the question of body mass in pterosaurs is addressed (Henderson 2010). In the most detailed study yet of pterosaur body mass, Henderson set out to explore this question and to compare the results to birds. He created a model of body mass based on modern birds by creating digital, three-dimensional models of their bodies. His model was corrected for differences in density from different areas of the body. For example, the wings will have a different average density than the trunk, where the volume of the lungs greatly impacts its overall density.

Using birds, he refined his model to accurately calculate their masses and centers of gravity. Then, he turned to the pterosaurs. What he found was very interesting. The pterosaurs in his study ranged from less than an ounce for Anurognathus to an astonishing 1,200 pounds in mass for Quetzalcoatlus (more on this in a moment).

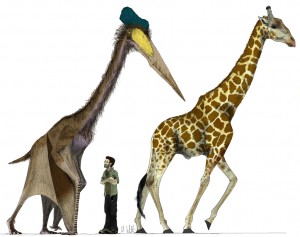

The giant pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus northropi compared to a modern giraffe. Illustration by Mark Witton.

Excluding the giant Quetzalcoatlus for a moment, the other heaviest pterosaurs were Pteranodon at 41 pounds and Tupuxuara at 50 pounds. The estimates for the ancient fliers are not too far off the masses of the largest modern flying bird the Great Bustard, at 35 pounds. So, we know that it is at least possible for an animal of that weight to get airborne on a regular basis.

So, what about the giant Quetzalcoatlus? This animal is known from fragmentary remains from Texas where it was first found in 1971. While mostly known from fragmentary remains it is estimated that it had a wing span of 37 feet or more. Earlier estimates of the weight of this animal vary widely from 141 – 608 pounds. Henderson points out that many of the body mass estimates of the past were influenced by engineering constraints calculated for an animal with this great wing span to be able to fly. The thinking being that an animal evolved from flying animals most likely flew.

But, in an interesting twist, Henderson’s estimate is twice as much as previous estimates, so he turns the issue around and suggests the heresy that maybe giants like Quetzalcoatlus (and I would add Hatzegopteryx by extension) did not fly. Instead, it is perfectly reasonable to assume that a formerly flying species secondarily adapted to a fully terrestrial life style, growing to dramatic size as a protection from predation or for other similar advantage. We certainly can find examples of that in the modern birds too, in the flightless ratites, the emus and ostriches.

No doubt this issue will continue to be explored (for an alternative view see [link id=’2475′]) . That is the fun of science—keep probing and answers, and more questions, reveal themselves.

Henderson, D. M. 2010. Pterosaur body mass estimates from three-dimensional mathematical slicing. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30(3):768-785.

Related Posts:

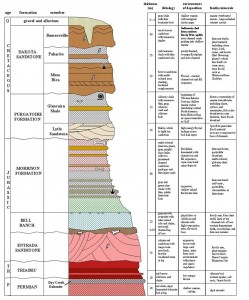

Formations

Niobrara Chalk

My National Geographic moment