A couple of innovations in aquariums might be something you wish to consider if you are thinking about getting an aquarium. Wall aquariums are those that are built into a wall and viewed from one or both sides of the wall. Wall-mounted aquariums are hung on the wall like a picture, and do not require aquarium stands. These unique aquariums can be very striking in a room, but are not without their challenges too.

Wall Aquarium

A true wall aquarium is an aquarium that can be variable in length and height, and is the same thickness, or very close to it, as the wall it is in. In most modern construction, interior residential walls are 4.5 inches thick, being framed with 3.5 inch 2 x 4 studs and covered on both sides with ½ inch drywall. You can install a wall aquarium in an existing wall, but it does take some carpentry skills to cut the wall opening, reframe the opening to hold the aquarium, and trim the aquarium on both sides to finish the look. You will also likely want to wire an electrical outlet into the wall opening so you can plug in lights, pumps, and aerators for the aquarium.

Access to the aquarium is usually done by lifting the hinged top trim board so you can feed and maintain the tank. However, there is not a lot of room above the tank in which to work.

One problem with both wall aquariums and wall-mounted aquariums is they are thin and have a small surface area of water compared to the volume. This means that the water cannot naturally replenish its oxygen supply easily, and so aerators are highly recommended for the fish.

If you choose to install a wall aquarium, find out if the wall you wish to mount the aquarium in is load-bearing. A load-bearing wall is part of the structural integrity of the building and helps hold up the roof. If you cut into a load-bearing wall and do not replace enough strength back into the wall with framing, you could have a very serious problem, like you roof caving in. If you are at all uncertain about what you are doing it is best to contact a professional.

If you are building a new home or addition it might be best to frame the wall from the start to hold the aquarium. This could save you a lot of hassle later on, but of course you have to plan ahead.

Wall-mounted Aquarium

A wall-mounted aquarium is far less permanent than one framed into the wall itself. This type of aquarium is hung on the wall, like a picture or other piece of art. In fact, many are designed to be living art.

The kits that come with wall-mounted aquariums show you how to mount them, and proper mounting is critical. The tanks are heavy, so the mounting needs to be into wall studs in order to support the weight without falling down. You should know how to locate wall studs before attempting to mount the aquarium.

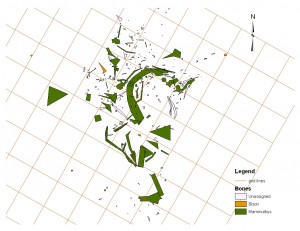

View of a wall-mounted aquarium showing the frame around the front, the background image giving it a detailed look, and the control panel on the side.

Stud placement within the wall may not be optimal for your desired placement of the tank, and this is a limitation of a wall-mounted aquarium. Perhaps you should make sure you can mount it where you wish before making the investment, because these aquariums are more expensive than normal aquariums. Also, the mounting brackets that come with the aquariums are designed for studs that are 16 inches on center, which is the most common framing standard in the United States. However, if your home is older, or the wall you wish to mount on for some reason does not have 16 inch on center studs, you may be out of luck.

You will need an electrical supply nearby for this type of tank too. A really clean-looking installation would have the cords hidden in the wall, but most commonly you will need to run the cord down the wall under the tank to the power outlet. It is a good idea to have the cord come down to the floor then loop back up to the power outlet in a “drip loop.” If water should run down the cord it will drip off at the floor and not run down the cord into the power socket—a recipe for a fire.

You will likely want to hide the power cord or disguise it somehow too. You might paint it the same color as the wall, install a cord channel of some sort, or artfully place decorations under the tank to hide the cord. A word of caution, the cord that comes with the tank kit may not be very long, and you may need to replace it or extend it. It is best to let someone who knows about wiring do this work.

Another note about placement, you really should have a minimum of 18 inches free space above the top of the wall-mounted aquarium so you have room to reach into the tank for cleaning.

Wall-mounted aquariums are all-in-one packages with lights, heaters, filters, pumps, aquarium backgrounds, gravel, and aerators already installed and controlled by an on-board computer. As such they remove the guess work from the set up. Also, they are supposed to be low maintenance, but they still require some regular attention. Some people have had issues with finding replacement parts, even for the light bulbs, for example, which might be a real consideration. It might be nice to take it out and plug it in, but something will break, and if you cannot replace the light bulb easily, your wall-mounted piece of art could become an expensive wall-mounted piece of junk.

With both wall aquariums and wall-mounted aquariums there are limitations as to the kinds of fish you can keep. As stated, the tanks are very thin, 4-6 inches. This means that you cannot keep fish that are going to get very large or they will not be able to turn around.

And all the basic information about setting up the tank, balancing the nitrogen cycle, and giving it a good breaking in period, and so on still apply to these tanks. You can find detailed information about setting up an aquarium in other posts.

One of these types of aquariums might be right for you. A wall-mounted kit can give you a very attractive tank without a lot of fuss, but you will pay for it up front as they are more expensive. In an office or home setting, it could be very elegant and a definite conversation piece.

A true wall aquarium likewise would be a great conversation piece, but commits you to significant modification of your home. It might well be worth it, but go into either of these options knowing the pros and cons.

Other aquarium-related posts:

Essential advice for setting up a home aquarium

Aquarium stands, options and considerations

Aquarium hoods