In this installment of the Dangerous Animals series we look at a group that is very misunderstood, and often erroneously indicted for being dangerous—spiders. In the summary chart of dangerous animals, summarized from various sources, spiders are accused of causing 6 deaths a year, on average, in North America. This is more deaths than caused by bears, mountain lions, and wolves combined, and I am highly suspicious of the figure.

In his review of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data, Langley (2005) summarizes death by all sorts of wild animals, and spider bites have their own classification code, suggesting that the medical community has decided it is worth watching for. For example, the data suggest that between 1991 and 2001 there were 5 fatalities by alligators, and a whopping 66 deaths by spider. People seem to be dropping dead left and right from spider bites. What gives?

In North America, there are two types of spiders known to cause medically significant envenomations in humans: the widows and the recluse. Let’s look at each.

Latrodectus, the Black Widow

Latrodectus, the black widow, showing a characteristic pose, upside down in the web.

There are currently 30 species of spiders within the genus Latrodectus, commonly called widows in North America. The species are distributed world-wide and are on every continent except Antarctica. The venom of the widow contains neurotoxins that inhibit neurotransmission. The spiders like dark and quiet places, with bites occurring when people unintentionally grab or sit on the spider, perhaps under a porch, on lawn furniture, in the tool shed, or in gloves or other item clothing. In the past bites sometimes occurred in outdoor toilets. Symptoms of bites tend to be local and radiating pain, and sometimes back, abdominal, and chest pain, sometimes accompanied by fever, agitation, hypertension, and interestingly, priapism (Vetter and Isbister 2008). People have described it to me like a case of the flu. Untreated, symptoms can last from hours to days. Despite their infamy, death is very uncommon.

Loxosceles reclusa, the Brown Recluse

Loxosceles reclusa, a Brown Recluse female guarding her egg sac on a cardboard box in Kansas.

Few spiders generate as much passion and aversion as the brown recluse (Loxosceles reclusa). I currently live in an area where black widows are extremely common, and local people are very casual about them, but are terrified of the brown recluse. I have done many educational programs where I have displayed live spiders, including black widows, and unvaryingly I am treated to several stories by visitors about how they (or someone they know) were bitten by a brown recluse, usually with very bad consequences. (I literally had one person tell me that his aunt had her entire arm removed because of a bite). The thing is brown recluse spiders do not live here! Nothing generates fear like the unknown.

Prior to living where I do now, I lived in an area with gobs of brown recluses, and the people there were generally nonchalant about their presence, as there were almost no cases of bites resulting in horrible wounds.

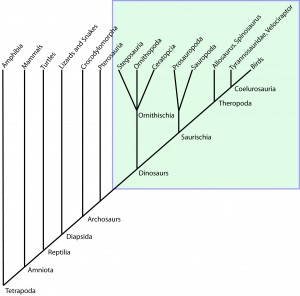

Distribution map of species within the genus Loxosceles, including Loxosceles reclusa, or the Brown Recluse (from Vetter 2008).

To be clear, Loxosceles is confirmed to have bitten people and caused wounds that in rare cases take a long time to heal and can leave disfiguring scars, or even death. They are a spider of medical concern. But, having said this, the threat is far over blown.

They are named “recluse” because they like very quite areas, and can frequent homes and storage sheds in quite places. They like corners of basements, and particularly cardboard boxes. Sometimes they crawl into clothing and shoes left on the floor or in the closet. Like with the widows, people are most often bitten when they catch the spider between their body and where the spider is—the bite is defensive.

In a majority of cases, the bite results in local discomfort and nothing more. In some cases a larger wound forms that is tender, but most of these heal with minimal medical intervention, usually within days. Sometimes the wound heals slower, and in rare instances does grow large and can leave a scar. And in very rare cases (<1%) there are more significant systemic issues that can affect major organs and cause death. (Vetter and Isbister 2008).

As mentioned, I lived in an area with known recluse populations. In fact, in one case, 2,055 individual recluse spiders were captured in 6 months from one home in Kansas where the family lived for many years without a single incident attributed to the spiders (Vetter 2008). However, popular perception about these spiders is very different. Why is this?

The most likely explanation is that when the recluse was implicated in bites the most extreme cases got widely reported, heightening awareness in the public and medical community. Diagnoses of recluse bites have become common place, often in areas where the spiders have not been found in the wild, and usually without clear evidence that the symptoms presented were actually caused by a spider, or any other bite for that matter. For example, in Florida, an area without a known population of recluses, during a six year period, 844 brown recluse bites were reported: 124 by medical personnel, 198 by people seeking information about bites, and 522 from people reporting bites treated at a non-healthcare facility (Vetter and Furbee 2006). Physicians are thus occasionally guilty of “practicing Arachnology” by identifying bites, and even spider species, from clinical symptoms alone. The truth is, there are numerous conditions that have been, or could be, misdiagnosed as a recluse bite (Vetter 2008) (see below).

Given the obvious over-diagnosis and misdiagnosis of spider bites, and of recluse bites in particular, I find the assertion that 6 deaths a year in North America are caused by spiders to be highly doubtful. At the very least, this is an undeserved slam against our eight-legged friends, and at worst is misleading the public and medical community, causing potential misdiagnoses and poor treatment choices.

Conditions that have, or could be, misdiagnosed as a bite from a brown recluse (Loxosceles reclusa), from Vetter 2008.

Infections

Atypical mycobacteria

Bacterial

– Streptococcus

– Staphylococcus (especially MRSA)

– Lyme borreliosis

– Cutaneous anthrax

– Syphilis

– Gonococcemia

– Ricketsial disease

– Tularemia

Deep Fungal

– Sporotrichosis

– Aspergillosis

– Cryptococcosis

Ecthyma gangrenosum (Pseudomonas aeruginosa)

Parasitic (Leishmaniasis)

Viral (herpes simplex, herpes zoster (shingles))

Vascular occlusive or venous disease

Antiphospholipid-antibody syndrome

Livedoid vasculopathy

Small-vessel occlusive arterial disease

Venous statis ulcer

Necrotising vasculitis

Leukocytoclastic vaculitis

Polyarteritis nodosa

Takayasu’s arteritis

Wegeners granulomatosis

Neoplastic disease

Leukemia cutis

Lymphoma (e.g., mycosis fungoides)

Primary skin neoplasms (basal cell carcinoma, malignant melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma)

Lymphomatoid papulosis

Topical and Exogenous Causes

Burns (chemical, thermal)

Toxic plant dermatitis (poison ivy, poison oak)

Factitious injury (i.e., self-induced)

Pressure ulcers (i.e., bed sores)

Other arthropod bites

Radiotherapy

Other Conditions

Calcific uremic arteriolopathy

Cryoglobulinemia

Diabetic ulcer

Langerhans’-cell histiocytosis

Pemphigus vegetans

Pyoderma gangrenosum

Septic embolism

Related posts:

See the rest of the Dangerous Animals series

Pesky house bugs–bed bugs

References:

Langley, R. L. 2005. Animal-related fatalities in the United States–an update. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine 16:67-74.

Vetter, R. S. 2008. Spiders of the genus Loxosceles (Araneae, Sicariidae): a review of biological, medical and psychological aspects regarding envenomations. The Journal of Arachnology 36:150-163.

Vetter, R. S., and R. B. Furbee. 2006. Caveats in interpreting poison control centre data in spider bite epidemiology studies. Public Health 120:179-181.

Vetter, R. S., and G. K. Isbister. 2008. Medical aspects of spider bites. Annual Review of Entomology 53:409-429.