Truth is stranger than fiction. The most recent human fatality caused by a bear took place in the wilds of Ohio. Well, sort of the wilds—just outside of Cleveland.

It seems that a young man, Brent Kandra, was tending to a captive bear when the bear attacked and killed him. The bear was owned by a man who has kept exotic animals for display in the past, and the event has sparked debate about the wisdom, and regulation, of large exotic animals being kept by private individuals (Associate Press 2010).

Whether in a cage or in the wild, bears are undeniably dangerous animals. This is the next in our series exploring dangerous animals. Unlike most of the other species we have looked at whose danger to humans is really more imagined than real, bears do come in contact with humans with some regularity, sometimes with unfortunate consequences.

In North America there are three bear species: the black bear (Ursus americanus); the brown bear (Ursus acrtos); and the polar bear (Ursus maritimus).

Black bear in the Canadian Rockies

Like so many common names, the name black bear is really not very good since the animals are often many other colors than black. The fur comes in shades of blond, black, brown, cinnamon, and gray. Interestingly, the bears tend to be black in the eastern forests, and more color variation is introduced as you survey the populations to the west, such that in California most of the bears are brown.

The black bear is the smallest of the bear species, and the most common, with the widest current distribution. They are found across Canada and south through New England into the Appalachian Mountains. There are populations in the Ozarks and in the southern states. In the west they can be found through the Pacific Northwest, and through the Rocky Mountains south into Mexico.

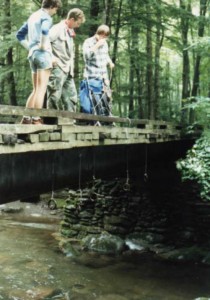

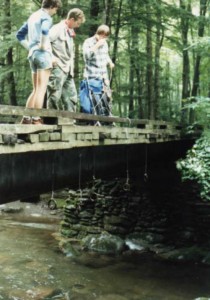

Black bears are generally shy and reclusive, but they can become accustom to humans, especially when they learn to associate human activity with food—through trash or handouts. In many backcountry areas where bears are common officials try to keep bears and people separate, but it is not always possible. Food storage is a great concern when camping. For example, while camping at one remote location in the Great Smoky Mountains campers were to hang their food from a cable over a stream.

Hanging a food pack over a stream in bear country

Incorrectly hanging your bag could lead to a bad time.

Results of improperly hanging your food pack

Brown bears are similarly misnamed, although the color variation is less dramatic than their black bear cousins. There are several subspecies, or races, of brown bears that you may have heard of, dividing them into coastal Kodiak and inland grizzly populations, but they are all the same species.

Brown bear

While once much more wide-spread in their distribution, brown bears are limited today to Alaska and northwest Canada, with several populations in western United States parks such as Glacier and Yellowstone.

Encounters with polar bears are understandably rare given the remoteness of their habitat. (See why polar bears are sensitive to climate change.) Polar bears spend much of their time out on sea ice, hunting seals. However, unlike other bear encounters, most encounters between humans and polar bears seem to be motivated by predation—that is, the bear is looking to eat them.

Bear encounters do sometimes lead to injury or even fatalities, and as people spend more time in bear country, the chances for an encounter naturally go up. In encounters that go badly, injury is more common than fatality as bears most often attack when they feel threatened, and once the threat is over they tend to leave. Rarely do bears prey on humans as a food source, but it does happen. In general there are about 1.8 bear-caused fatalities per year (see Clark 2003, Gunther and Hoekstra 1998, Herrero and Fleck 1990, Herrero and Higgins 1999 for discussions).

Of the dangerous animals discussed in the series, bears are the ones that most people need to be aware of, and to think about when entering the woods. Do not do stupid things in bear country, like walk around imitating the sounds of animals to attract bears (yes, it has happened), improperly store your food, try to feed the bears, get too close while taking pictures, or tease or taunt the bears. Common sense and awareness that these majestic creatures are sharing our woods will ensure that your adventures will have only the typical amount of excitement.

Associate Press. 2010. Bear who mauled caretaker is put to death in Ohio. NPR. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=129321688.

Clark, D. 2003. Polar Bear – human interactions in Canadian National Parks, 1986-2000. Ursus 14(1):65-71.

Gunther, K. A., and H. E. Hoekstra. 1998. Bear-inflicted human injuries in Yellowstone National Park, 1970-1994. Ursus 10:377-384.

Herrero, S., and S. Fleck. 1990. Injury to people inflicted by Black, Grizzly or Polar Bears: recent trends and new insights. Bears: Their Biology and Management 8:25-32.

Herrero, S., and A. Higgins. 1999. Human injuries inflicted by bears in British Columbia: 1960 – 97. Ursus 11:209-218.