In the twenty plus years I have been involved in paleontology I have been witness to a revolution within science. The revolution has been quiet, not noticed by most of the public. Like any good revolution, the battles of this revolution took place between two camps, the “traditionalists” and the “radicals” who were out to change things. And this shift is illustrative of how science as a whole moves from one way of understanding to a brand new way of looking at the world. It is, in fact, a paradigm shift that has profoundly changed biology and paleontology forever.

At issue is how we explore and classify the relationships of all living things. The traditional view, the one that I was taught as a young student, was the classification of living things into the taxonomy originally begun by Carl Linnaeus. This system started with a group, and then sought to put things into the group. For example, one can make the observation that animals that look like “dogs” could be grouped together, so you would start with the idea of a dog-group and look for animals that should be included.

You might put foxes, wolves, domestic dogs into the group, and call it the dog family. You might also note that “cats” could likewise be grouped, and do the same thing, creating a cat family. In this view, the families were equal in rank—and there could be no overlap. An animal would be included in only one of the equal-ranked families. Any animal was included in only one class, for example Amphibia, Reptilia, Aves, or Mammalia.

The equal-ranked heirarchy of classifications worked well enough when we mainly were concerned with modern animals. Clearly, birds look different than mammals and reptiles, so it seemed evident they belonged in their own class. But this classification scheme, however well it served us as a place to start, is myopic about how evolution actually operates—how organisms actually evolve. This is understandable since it was started 100 years before evolution as a theory was established.

In trying to shoehorn life into the system, we repeatedly ran into problems as we expanded our knowledge of the diversity of living things and our understanding that the history of life is a complex branching bush. We knew that early tetrapods (organisms with four limbs) gave rise to the early amphibians that crawled out on land, and that they in turn evolved into reptiles, mammals and birds. But despite this branching within tetrapods, the class ranks were forced to be exclusive, so somewhere in evolutionary history was an “amphibian” that had to become a “reptile,” and a “reptile” that had to become a “bird.”

The many transitional forms in the fossil record increasing became impossible to classify. These intermediate animals had to be forced into one class or another. Increasingly, it became evident that many times the criteria used to put an organism into one class were the whims of an individual scientist, and another equally qualified expert with different opinions might place the same animal in a different class with equal validity.

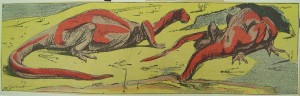

The origin of birds was for a long time a great mystery to paleontologists. Birds are a pretty unique and specialized group, and while we knew that they originated from reptiles somehow, exactly how and when was unclear. One early paleontologist noted that dinosaurs had many features in common with birds, but the early concepts of what dinosaurs were like distracted most scientists from comparing them too closely. After all, the common conception of dinosaurs was as big, lumbering, dim-witted, swamp-dwelling beasts. The bird ancestor must have been light, fast moving, and energetic.

However, dinosaur research over the last thirty years has completely changed our view of them. Evidence from many lines, including things like footprints and the cellular structure of the bones, all point to dinosaurs as being very dynamic creatures. With this new view, the notion that birds were linked to dinosaurs became clear too. Now, we have dinosaur fossils with feathers, and birds with teeth and dinosaur tails to attest to their close relationships. In fact, birds are most closely related to the meat-eating raptor-like dinosaurs of Jurassic Park fame.

To go along with the revolution in our view of dinosaurs was that revolution in science that I mentioned above–the emergence of a new way to understand the interrelationships of life on Earth. This new model accommodated the myriad branching events that life actually experienced in order to produce the great variety of living things. So, instead of starting with a conception of the group and looking for members, this new concept looked at the branching patterns evident in life, and then sought to apply names.

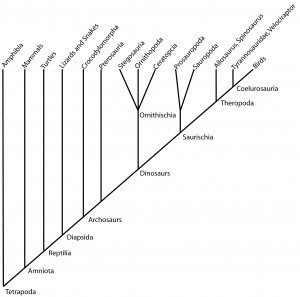

Below is an illustration of the branching pattern of selected tetrapods, those vertebrates with four well developed limbs. As the first tetrapods gave rise to new and different groups, the branches split off. An early tetrapod gave rise to amphibians and the other animals above it on the chart (mammals, turtles, etc.). A later tetrapod developed traits related to the production of eggs and young that we recognize as the Amniota. Some of those early amniotes went off on an evolutionary trajectory that we can recognize as being the early mammals, and all the diversity that resulted from them. And so it goes up along the branches.

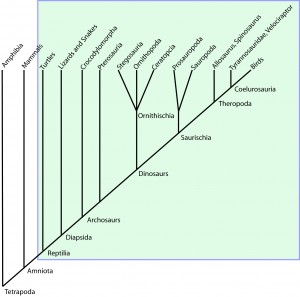

We now explore the branches and can apply names to the groups that we find to be meaningful. For example, in the illustration below we can call everything in the box a reptile. Note that it includes things that used to be called reptiles, turtles, lizards, snakes, crocodiles, and dinosaurs, but now also includes birds.

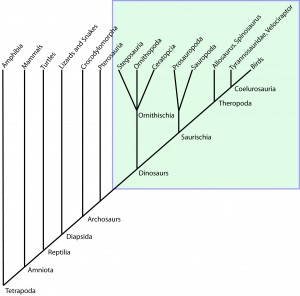

Likewise, if we draw a line around the dinosaurs, they also include the birds. This view of life tells a more complete evolutionary history and retains the branches, letting the animals “fall where they will.” We do not pull birds out of their relationships and give them special consideration. Instead of birds being equal in rank with reptiles, they are included among them. This upsets the tradition that being a bird is somehow equally important to being a reptile, but better reflects the reality of descent, without forcing nature into earlier human conventions of naming and grouping. Of course, birds are a group within their own right, and we could zoom in to explore their branching pattern, but it does not change the group to which they belong.

This leads to another startling statement. Below I have highlighted the groups that are extant (still around today).

Because of our grouping scheme, birds are included in the dinosaur group, so dinosaurs are not really extinct! They live among us today flitting about, singing their mating songs in the trees. It is funny how things can change in science. Twenty years ago scientists would have told you the dinosaurs were all extinct, and today we say the opposite. I love scientific progress–it can be so startling.