The topic of climate change is complex and politically charged—two characteristics that guarantee confusion in the general public. Increasingly, the subject of climate change is emerging as a partisan issue, once again dividing Republican and Democrat.

A recent Gallup poll shows that Americans are becoming increasingly less concerned about the threat. Forty eight percent of Americans believe that the seriousness of climate change is exaggerated, up from 41% in 2009 and 31% in 1997.

The doubt in public opinion is not reflected in the scientific community, however. The national science academies of all the major industrial countries have issued statements about the reality of climate change and the role of human activity in creating the change (Wikipedia).

Even if we want to assume that all public doubt over climate change is honestly acquired, a position that I do not hold, perhaps the general public can be forgiven in some measure because the issue is complex, and like every other issue in science contains degrees of uncertainty. One of my favorite quips is making predictions is tough, especially about the future. I would like to borrow that and say that making predictions is tough, especially about the past—the geologic past that is.

Huge advances have been made in recent decades in understanding past climate systems of the Earth. The picture that is emerging with increasing clarity is that the Earth and all the systems that affect climate are dynamic and complexly interrelated. A good summary of what is known about climates of the past can be found in the latest IPCC report (Jansen et al. 2007).

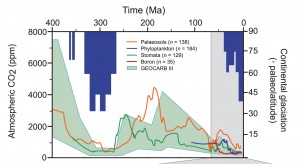

Of significance is the evidence that global climate trends track closely with the levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide—a pattern that is 400 million years old. The prehistoric levels of CO2 can be directly measured from ice cores for almost the last 1 million years. Before that, we obtain estimates of CO2 levels by examining proxies, things that we can measure directly within fossils or the geologic system that reflect CO2 levels indirectly.

It is like estimating a family’s income by looking at the house they live in—certainly not a perfect system, but a proxy that in general will work as we do tend to display income prosperity through home selection.

The proxy data of CO2 levels through geologic time show those periods of low concentrations correspond with periods of increased glaciation, with peaks in glacial activity around 300 million years and again in more recent times with the last Ice Age. Both those periods had lower CO2 levels. Between those periods, CO2 was high, much higher than today, and average global temperatures were much higher as well. Areas of the Earth today that are temperate were often inhabited by plant and animal species that we only find today in more tropical environments.

Shaded area and the colored lines show various proxy estimates for CO2 levels over the last 400 million years. The blue bars represent periods of glacial activity. During times of low CO2 concentration temperatures were also low with ice accumulation.

Does this mean that since CO2 levels in the past were much higher than today (and higher than even predictions for the next century or more of increased carbon emission) that we can be unconcerned? The Earth has seen much higher levels of CO2 and much higher average temperatures in the past, after all.

True, but that misses the point. The point is not that we are setting up environmental conditions that are unprecedented in geologic history. The point is that the rapidity of the change we are seeing today is without precedent and is anticipated to cause natural and social changes of significant consequence.

In the past, plants and animals could respond to fluctuation in climate because the changes occurred slowly. Organisms either changed their range to stay with favorable conditions, evolved to meet the new demands of their environments, or went extinct. But they did it on geologic time scales of hundreds of thousands, or millions, of years.

The modern changes driven by human activity are causing very rapid changes, on the order of decades to centuries, and natural systems are in a crisis of adaptation. And the bigger issue is that the ecosystems of the Earth are interrelated in complex ways, such that changes will inevitability have a ripple effect. Those are the same ecosystems that we depend upon for our food, water, and other resources, and that we have built our economies on.

There are several dimensions to the crisis of global climate change. One is a crisis of nature. Charismatic species like the polar bear are threatened, but the world will not collapse when the polar bear goes the way of the dinosaur. Although I think a strong case can be made that we have some moral obligation to not stand idly by while it happens, it may be “no skin off our teeth” to have a world without polar bears.

Consider the analogy of an airplane in flight. As we fly along we could go around the structure of the airplane and pop out the rivets that hold it together. No doubt we can take out one here, another one there, and the plane will stay aloft. But if you are in the plane, how many will you be comfortable losing? At some point, you take out enough rivets and the plane will fall apart.

The loss of the polar bear is only a single rivet. But there are hundreds, even thousands more that are likely to be lost through the effects of climate change. How long before the complex systems that we rely upon come falling out of the sky is an open question—we do not know.

However, I think the real vexing issues we face are the social and political issues, which are far thornier. What actions should we take to mitigate CO2; who should pay for it; what will the effects be on developing and low-lying countries and who should take responsibility; what are our obligations to developing economies; how aggressively should we make a transition to non-carbon-based energy systems, and who will pay, and who stands to lose; how will climate changes affect agriculture, water supplies, and the general balance of political power? Questions like these are not scientifically based—they are economic, political, or moral decisions, and are the real issues of the public climate change debate.

Those who want to confound the issue for political gain often resort to throwing mud at the scientific debate, pointing to known uncertainties of the models, or dredging up scientists who are dissenters, or other similar political “gotcha” tactics. Evidence suggests that they are succeeding—the public is less certain about the reality of climate change, and the political parties are capitalizing on their confusion. This may make good political theater, but I think that this level of discourse diminishes us all.

Perhaps it is too much to hope for that we have intellectual integrity in public debate, but I keep hoping. I think Thomas Jefferson said it best, “If we are to guard against ignorance and remain free, it is the responsibility of every American to be informed.”

Gallup Poll: Americans’ Global Warming Concerns Continue to Drop

Jansen, E., J. Overpeck, K. R. Briffa, J. C. Duplessy, F. Joos, V. Masson-Delmotte, D. Olago, B. Otto-Bliesner, W. R. Peltier, S. Rahmstorf, R. Ramesh, D. Raynaud, D. Rind, O. Solomina, R. Villalba, and D. Zhang. 2007. Palaeoclimate. Pp. 433-497. In S. Solomon, D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K. B. Averyt, M. Tignor, and H. L. Miller, eds. Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, New York.

Wikipedia–Global warming controversy