One of the most exciting things in paleontology is being able to definitively establish the interaction of two species from the fossil record. It is thrilling to picture a moment in time, millions of years ago, when two animals were at the same place, at the same time, and be able from fossil evidence to glean something about their interaction and behavior.

One dramatic example of this is finding a fossil with clear evidence that it was bitten by a shark. During the Late Cretaceous, North America was cut in half by an interior sea that extended the Gulf of Mexico across the mid-continent to connect with the Arctic Ocean in the north, effectively creating two land masses where today there is one.

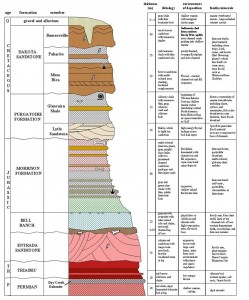

In this last period from the Age of Dinosaurs, fantastic and strange creatures swam the seas. Today, the sediments from that ocean are exposed in badlands across much of western Kansas, Nebraska, and South Dakota. These geologic formations, like the Niobrara Formation, preserve a rich record of the ocean life, and clearly show what a scary ocean it was.

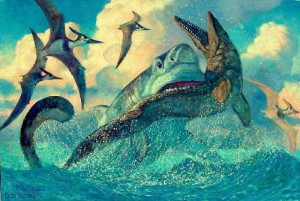

Giant marine lizards thrived in the sea. These beasts, close relatives of modern snakes and lizards, were called mosasaurs. There were several kinds that likely had different modes of life, some making use of resources close to the surface, and other species specializing in deep-water feeding, with the largest of them reaching 50 feet in length. They were joined by another group of marine reptiles called plesiosaurs. Plesiosaurs occur in two basic body plans, with the unimaginative names of long-necked and short-necked for obvious reasons.

The long-necked plesiosaurs have been described as looking like a turtle with a snake threaded through its shell. They had a stocky, turtle-like body, enormously long necks capped by a remarkably small head, and stumpy tails. They had four large flippers that helped to propel them through the water as well.

Short-necked plesiosaurs had large heads attached to short, thick necks. The long-necked forms most likely specialized in eating smaller fish with their small heads, maybe using their long necks to “snake” their way amongst their prey before being noticed. The short-necked forms obviously ate large prey, as evidenced by their massive heads and powerful jaws. (You can find models of both long and short-necked forms, as well as mosasaurs as part of the collection of dinosaur toys).

Living alongside these giants of the sea were animals that we would easily recognize, at least for their general body plan—these were the sharks. There was a significant amount of shark diversity in the Interior Sea as well, from relatively small forms that likely ate near the sea floor, to mid-sized forms that ate smaller fish and scavenged on dead carcasses, to several very large species that rivaled the modern great white shark in size and ferocity.

On occasion, when finding remains of fish or the marine reptiles, we find evidence of those remains having been bitten by sharks. The most compelling evidence is when teeth are found embedded in the fossil remains, but also punctures and tooth scratches can be a telltale sign.

Several plesiosaurs have been found as partial skeletons, with bites in several areas of their body, suggesting that after they died and settled to the ocean floor their carcass was scavenged by mid-sized sharks.

And in one dramatic example, the great white of the Kansas seas bite the back of a mosasaurs, cutting a section of vertebrae completely out of the giant lizard. The section of back, with its included vertebrae, was later spit out by the shark after having been mostly digested. The gristly remains settled to the ocean floor to lie there for millions of years before being found and placed in a museum.

Today we are fascinated by tales of shark attack, with the movie Jaws being a prime example. You can learn about these dangerous animals in another post, but perhaps it gives you some comfort to know that the denizens of the ancient seas also were subject to shark bites!

Additional information about this specimen can be found at Oceans of Kansas.