“A photographer from National Geographic wants to talk to you.” These words, or words to those effect, met me as I came into the museum office one day back in 2001, and they definitely caught my attention.

It was 2001 and I was Assistant Director of the Sternberg Museum of Natural History. We had just reopened the museum in its new location in Hays, Kansas, a few years before in 1999. The museum had enjoyed some tremendous success at attracting visitors and media attention from across the state. And now someone from National Geographic wanted to talk to us? Wow. I returned Jonathan Blair’s call and began an unusual week of activity.

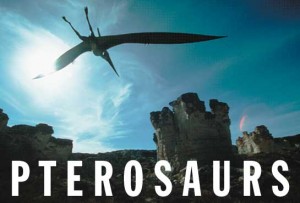

It turns out that the magazine was going to run a story on pterosaurs, the flying reptiles from the Mesozoic, and they hired Jonathan to get pictures to illustrate it. He had already traveled to some of the great museum collections for pterosaurs in Europe and the United States, but he wanted to visit Sternberg. The Sternberg’s collection of pterosaur material is about the third or fourth largest in the nation, and very significant.

The Sternberg Museum, on the campus of Fort Hays State University, was managed for many years by George F. Sternberg, famed fossil collector. He spent his free time out in the chalk, the Niobrara Formation of western Kansas, collecting the fish and swimming and flying reptiles that left their remains millions of years ago. Sternberg supplemented his salary at the museum by selling specimens to other museums, but if he collected something really nice it went into “his” museum. Over the years, the museum’s collection grew in size and quality.

Besides our amazing collection of fossils, Jonathan had heard about our life-sized pterosaur models we had just installed in our walk-through Cretaceous exhibit. And he had a crazy idea—let’s take a life model of the beast and “fly” it over the very rocks where its remains can be found. He wanted to take one of our life-sized model and photograph it over the chalk beds.

Well, I can bend over backwards for National Geographic, but taking one of our brand new models down from the ceiling, which had not been easy to install in the first place, and which since had walls built up around them, and truck them 70 miles to hang from a crane in the chalk sounded a bit risky to me.

But I did offer to help in any way we could, so I did the next best thing—I found him another pterosaur model.

Over the next several days we made plans and preparations for the big event. We needed to get the model that I was able to find shipped to the museum. It had been kept in storage and was a little beaten up, but the company that supplied it sent a staff member to clean, fix it, and touch up the paint for its big moment. The model, being life-sized, had a twenty foot wing span, flimsy neck with a large head at the end, and feet that stuck out the back, giving the whole thing a cross shape, making it too long in any direction. Not exactly the easiest thing to get into a truck and ship!

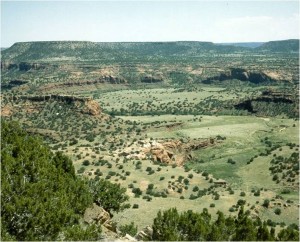

We scouted a location for the big photo shoot. I took Jonathan to the Castle Rock area, a well-known outcropping of the chalk that has easy access and grand vistas. We needed to secure special permission as we were going to bring in a crane and another truck to transport the pterosaur model.

We needed to arrange for a crane to make the 70 mile one-way trip from Hays to the chalk beds. On this, and on so many other occasions, I marveled at the “can do” spirit of western Kansas people. You want something done just ask a former farm kid. While he might look at you funny, he will get it done.

In between all this activity, I remember some spectacular meals shared with Jonathan, listening to his many adventures from around the world while taking photographs. He also shot pictures around the museum, and he took a couple of photos of me that I have cherished ever since.

Greg dusts the life-sized models of Pteranodon sternbergii at the Sternberg Museum of Natural History. Photograph by Jonathan Blair.

The big day arrived and all was going well. The weather cooperated, the truck was loaded with its ungainly cargo, and the crane made it to the site. We had also brought along a number of crew members to help hold the model. We wanted to lift it into the air for the photograph, but if you know anything about western Kansas, you know it is windy. I was not sure what would happen when you lifted such a thing into the gusty winds, and how hard it might be to control. The only control we had were guy-wires coming down from the wing tips to hold it against unruly behavior.

With trepidation we gave the signal to the crane operator to lift, and the hundred pound model took to the air. And in the end, the wind was no issue—the model, like the animal it represented, was built for the air. It found a comfortable equilibrium and settled into the wind easily. Jonathan snapped his pictures, and just like that we had what he had come after.

We took more photos at a few other locations, all of which could have made fantastic desktop images, but he knew he was done. We packed up and came home, and all those days preparation resulted in the lead image for the story. It was all Jonathan’s photo and idea, and I enjoyed the part I played in making it happen—one of the perks for working at a museum.

See the National Geographic story.

Related Posts

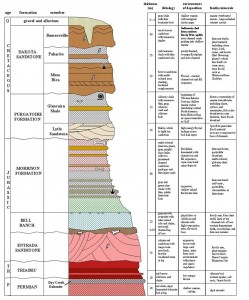

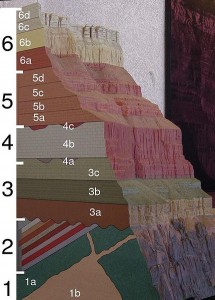

Geologic Formations