Mosasaurs lived in the world’s oceans during the Late Cretaceous, the last Period from the Age of Dinosaurs (see the geologic time scale). They are close relatives of modern snakes and lizards, and during the Cretaceous they become fully aquatic sea monsters, growing to tremendous sizes, and were the top predators of their environments.

Their fossil remains occur in great numbers in the marine chalk deposits of the Central Plains, and numerous specimens have been preserved in museums all over the world (see posts on the chalk formation and on rock formations in general). Yet despite the great numbers of specimens collected, we still have much to learn about these great beasts.

For example, examination of their bones shows that they are elongate animals, with enlarged tails for propelling their bodies through the water. Their limbs are modified into flippers, useful in controlling the direction and orientation of their bodies in the fluid medium. So, it is clear that they are primarily tail-swimmers.

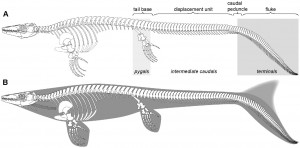

Early restorations based upon this evidence imagined a tail sort of like a modern crocodile, a thick tail that was slightly compressed laterally, making it taller than thick, but remaining relatively snake-like. Early restorations of the skeleton articulated the tail as a long chain of vertebrate, continuous from base to tip without any remarkable difference along the way.

Here is an illustration of the skeleton of the mosasaur Platecarpus from a classic work on mosasaurs (Williston 1898). Note the rod-like straightness of the back.

And here is an artist’s illustration of Tylosaurus, the largest of the mosasaurs, from Mike Everhart’s Book, Oceans of Kansas, showing the tail with a slight thickening near the end, but mostly being straight (Everhart 2005, recommended in the Boneblogger store).

However, frequently the skeletons of mosasaurs were found preserved in the rock with the last third of the tail bent downward, away from the main axis of the base of the tail. And this was not just found in a few skeletons, but it was found frequently enough that scientists speculated, at least in conversations with each other, that perhaps the down turned tip was not an artifact of preservation, but maybe meant something.

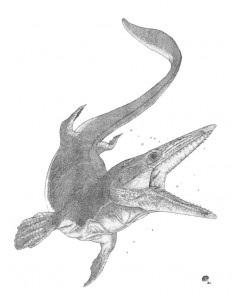

Well, a newly described mosasaurs fossil, which has exceptional preservation, provides the answer. This specimen collected in Kansas and now at the L.A. County Museum, preserves not only the bones, but also impressions of skin, impressions of internal organs, and even some of the body outline. The bones of the tail are clearly down-turned, giving the authors of this new study enough confidence to state what has been quietly talked about before—mosasaurs had a bi-lobed tail fluke (Lindgren et al. 2010).

It only takes a single fossil to help overturn past notions about prehistoric life. The next big discoveries are out there, in the rocks and sitting in the museum drawers, waiting to be examined in detail. What will we find next?

Everhart, M. J. 2005. Oceans of Kansas: A Natural History of the Western Interior Sea. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Lindgren, J., M. W. Caldwell, T. Konishi, and L. M. Chiappe. 2010. Convergent evolution in aquatic tetrapods: insights from an exceptional fossil mosasaur. PLoS ONE 5(8):e11998.

Williston, S. W. 1898. Mosasaurs. University of Kansas Geological Survey 4(1):81-347.