As the old saying goes, looks can be deceiving. That is the theme of a new paper on the Giant Short-Faced Bear (GSFB), Arctodus simus, recently published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology (Figueirido et al., 2010).

We have explored this beast in other posts (see below), and will no doubt do so in the future, as it is one of my favorite animals because of the fascinating paradoxes that it presents. Bears as a group often do not do what we think they should do!

The GSFB is the largest mammalian carnivore known, fossil or recent. First discovered in Northern California and described by Cope in 1879, remains of this species have since been recognized from Alaska to Mexico, and from the west coast east to Pennsylvania in North America. It lived from about 1 million years to about 10,000 years ago. It is likely that they became extinct as an ultimate effect of climate change at the end of the Ice Age.

Kurten (1967) was one of the first to look at the GSFB in much detail, and he made a number of observations that have come to define this bear: shortened face like a cat, and extremely long limbs compared to body length. Kurten argued that those adaptations show a hypercarnivore, a cat-like giant predatory bear, with long runner’s legs and a bite-style like the large cats.

There is something very appealing in this picture: a huge cat-like bear running down prey and dominating the Ice Age landscape. Alas, science cannot be based on drama or romantic notions, and this image of the GSFB gets reexamined from time to time, with other authors coming to different conclusions. Some have pointed out the ambiguity of the limb proportions, or compared the GSFB to its closest living relative, the South American spectacled bear, and concluded that it was primarily omnivorous with a diet rich in plants (Emslie and Czaplewski, 1985).

The question of what the GSFBs were eating, at least, seemed to have been dramatically concluded in a couple of papers during the mid-1990s (Bocherens et al., 1995; Matheus, 1995). Those authors explored the carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes preserved in skeletal material. You are what you eat as differing amounts of these elements are deposited in body tissues depending on their dietary sources, and the isotope data clearly show that the GSFB were eating mostly meat in their diet.

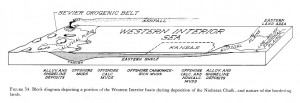

In the most recent paper, Figueirido and colleagues also re-examine Kurten’s cat-like interpretations of the GSFB. For example, they challenge the very notion that the GSFB was short-faced at all. While a casual observation of the skull seems to “bear” that out, they compared the skull and face length with other bears, and it seems that what makes the skull of the GSFB look short-faced is really the depth of the snout and the height of the skull overall, creating an illusion of short-facedness.

Snout lengths relative to skull length in living bears and in the GSFB.

They also ran a number of statistical analyses on the dimensions of the skulls of bears with other carnivores to see if differences in feeding behavior might be teased out this way. Feeding strategy, such as cat-like hypercarnivory or hyena-like bone-crushing, might be visible in the skull proportions. They concluded that the GSFB had a skull shape not like that of a cat, but more similar to modern brown bears (Ursus arctos). Brown bears are omnivorous and will certainly eat meat, but also have a significant amount of plant matter in their diet. So, those authors suggest the skull shape does not support a hypercarnivorous behavior.

Figueirido et al. also examined the claim that the GSFB had extremely long legs. They compared total limb length to overall body weight among modern bears and the GSFB. Their results suggest that the limb length is just what it should be for a bear of the overall size of the GSFB, and not especially long when compared to other bears.

Nothing in science is sacred and I applaud Figueirido et al. for critically looking at past interpretations. However, the answers to our questions continue to elude us. If they are right that the GSFB was not especially short-faced, and that the limbs were not especially long, and the skull was not especially cat-like, none of that really nails down the behavior of this giant species, as they point out. And bears in particular have a tremendous range of feeding adaptations and behaviors that do not fit the mold.

For example, modern bear behavior goes from one extreme represented by the polar bear, which lives on the arctic sea ice and eats almost nothing but seals, to the giant panda living in Asian forests and eats almost nothing but bamboo (but they too will eat meat if given the chance). And between those extremes is a lot of variation. There is really no reason to think that the GSFB was not also variable in its diet and behavior to some degree. But the isotope evidence is hard to argue with at the moment: they seem to have eaten a lot of meat.

The question remains though, how did they get their meat? Did they chase down their prey in long pursuits, or ambush them from short range, or act as the neighborhood bully and chase smaller carnivores from their kills? We don’t yet know but we will keep looking.

Related Posts:

GSFB, a North California Original

Denning Behavior in the GSFB

How Big was the GSFB?

Polar Bear Populations

BOCHERENS, H., S. D. EMSLIE, D. BILLIOU, AND A. MARIOTTI. 1995. Stable isotopes (C13, N15) and paleodiet of the giant short-faced bear (Arctodus simus). Comptes Rendus de l’Acadƒemie des Sciences Paris, 320, serie IIa:779-784.

EMSLIE, S. D., AND N. J. CZAPLEWSKI. 1985. A new record of giant short-faced bear, Arctodus simus, from western North America with a re-evaluation of its paleobiology. Contributions in Science, 371:1-12.

FIGUEIRIDO, B., J. A. PEREZ-CLAROS, V. TORREGROSA, A. MARTIN-SERRA, AND P. PALMQVIST. 2010. Demythologizing Arctodus simus, the ‘short-faced’ long-legged and predaceous bear that never was. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 30(1):262-275.

KURTEN, B. 1967. Pleistocene bears of North America; 2. genus Arctodus, short-faced bears. Acta Zoologica Fennica, 117:1-60.

MATHEUS, P. E. 1995. Diet and co-ecology of Pleistocene short-faced bears and brown bears in eastern Beringia. Quaternary Research, 44:447-453.