In modern oceans, the very largest organisms specialize in filter feeding, or living on the very small plankton in the water. (Read more about the filter feeding niche). Up until now, it has appeared to researcher that during the Age of Dinosaurs, when the oceans were dominated by large, toothy reptiles, there were no marine animals specializing in the niche of large-bodied filter feeding, despite ample evidence that the oceans were rich in planktonic resources.

However, this niche was in fact filled during the Mesozoic as demonstrated in a recent paper in the journal Science (Friedman et al., 2010). Turns out that several species of fish did specialize in filter feeding, and they too grew quite large. Most of the specimens were already sitting in drawers in museums, having been misunderstood for many years, until Friedman and his colleagues re-evaluated them.

For example, one species has been known for over 100 years—having been named by E. D. Cope in 1873 as ‘Portheus’ gladius from a specimen collected from the Niobrara Chalk formation in western Kansas. The Niobrara Chalk was deposited during the Late Cretaceous period (see a geologic time scale). The species has a long and complex taxonomic history, mostly of interest to professionals, but it does clearly show that many scientists reviewed the fossil material and scratched their heads in wonder about this strange set of fossils.

Friedman and his colleagues have finally put the pieces together, and it fills in much about the history of life in the oceans. They have created a new genus in which to place the species, so now it is known as Bonnerichthys gladius. The genus was named for the Kansas fossil-collecting family that collected the most complete specimen found to date.

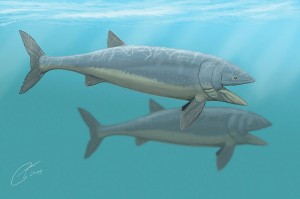

Bonnerichthys would have been about 20 to 25 feet in length with a huge, gaping mouth. You can see an artist’s reconstruction of Bonnerichthys at Oceans of Kansas. And you can listen to an interview with Matt Friedman at NPR.

This discovery opens up a whole new understanding of the paleoecology of the Mesozoic oceans, and shows that filter feeding was utilized for at least 100 million years longer as a major life strategy than previously recognized.

FRIEDMAN, M., K. SHIMADA, L. MARTIN, M. J. EVERHART, J. LISTON, A. MALTESE, AND M. TRIEBOLD. 2010. 100-million-year dynasty of giant planktivorous bony fishes in the Mesozoic seas. Science, 327:990-993.