One of the many places that I have been fortunate to spend time in is Purgatoire. Perhaps not the same thing you are thinking, but I am referring to the Purgatoire River Canyon in southeastern Colorado. Located south of La Junta, this area is an often-overlooked gem. The scenic vistas could be used for your desktop wallpaper!

Purgatoire River Canyon in southeastern Colorado

The many names applied to the region can be confusing. The Purgatoire River has cut a dramatic canyon in this part of the plains, and with the Rocky Mountain Front Range far to the west, it can be almost startling to come upon the deep canyon in an otherwise rolling plains landscape. Anglo settlers bastardized the name of the river, and instead of the eloquent Purgatoire, ended up calling the area Picket Wire, so both names alternately apply.

The area is managed predominately by two federal agencies, the United States Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service and the Department of Defense through the Army. The military uses their lands for maneuver practice, as I understand it, tanks and other mechanized equipment. Some years ago the Army carved off some of their land and gave it to the Forest Service to manage as part of the Comanche National Grassland. The Forest Service land is used for recreation and also the preservation of significant historic and prehistoric resources.

Petroglyph of human and horse figures

Rourke Ranch house in the Purgatoire Canyon

The historic resources include Native American petroglyphs and other archeological sites, early Spanish homestead sites and churches, early American homesteads. The prehistoric resources include dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals, both body fossils and trace fossils. I was very fortunate to have been involved in the documentation of some of the first dinosaur fossils from the region (Schumacher and Liggett 2004).

Dinosaur trace fossils, in particular dinosaur tracks, are well preserved in one section of the Morrison Formation in the bottom of the canyon. These tracks were discovered in 1935 by a young girl as can be seen in this newspaper clipping from the Topeka Capital Journal. However, the tracks are most definitely not those of a Tyrannosaurus rex (mentioned in the clipping) as that beast did not stalk the Earth for at least 90 million years after the track-makers walked here. This track site is the largest continuous track site of dinosaurs known from North America, and contains over 1,400 prints.

Newspaper clipping announcing the discovery of the Purgatoire track site

However, because of the remoteness of the site, scientists turned their attention to other dinosaur tracks found in Texas, and the Colorado tracks were essentially forgotten for many decades. However, a newer generation of scientists have re-examined the track site. Of interest is the fact that the site shows five parallel sauropod tracks, suggesting that at least in this case, the animals walked along together spread out, not walking in a line (Lockley 1991).

There are actually several track layers in the rocks. Also preserved are several three-toed theropod, or meat-eating dinosaur. While it is difficult to exactly match the track to the species of dinosaur that made them, the large sauropod tracks were made by an animal like Apatosaurus (Brontosaurus of old) and the meat-eating tracks are similar to what an Allosaurus would make.

A well-preserved theropod dinosaur track in the Purgatoire Canyon

View of the Purgatoire River track site using low altitude photography

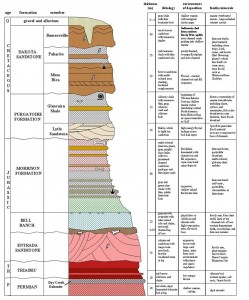

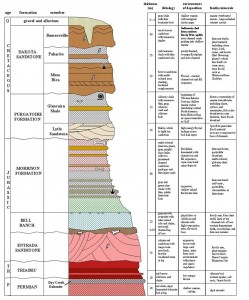

In addition to the tracks, the canyon is also now yielding body fossils of dinosaurs. It is really no surprise since the Morrison Formation is extensively exposed along the river canyons. The Morrison is the name given to a wide-spread formation that is the most prolific producer of Jurassic dinosaurs in North America. The formation outcrops in North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and Idaho. Every Jurassic dinosaur you have ever heard of comes from the Morrison; animals such as Allosaurus, Apatosaurus, Diplodocus, Stegosaurus, and Camarasaurus all come from this formation. (See Formations for information about what that means.)

Stratigraphic section of the Purgatoire River Canyon showing the geologic formations that outcrop

Given the Purgatoire River’s remoteness, and the fact that it was controlled for many years by the Army, few people were able to explore the region until more recent decades. Thus, now it is one of the last areas of the Morrison Formation exposures to be explored. And it is proving to be as rich as expected.

Over the last decade, the Forest Service has been conducting Passport in Time (PIT) programs in the canyons, looking for new dinosaur sites, and excavating sites. Many people, scientists, graduate students, and the lay public have enjoyed excavating dinosaurs in this beautiful and remote canyon. And several significant specimens have come out of the area. The Forest Service has partnered with many museums from the region to study this treasure-trove and to allow people to enjoy this amazing region.

Volunteers excavate dinosaur fossils from the Woody site

Dinosaur vertebra from the Woody Site being prepared at the Sternberg Museum of Natural History

Plastered dinosaur bone being carried out of the LC Site

Volunteers excavate dinosaur bones from the Morrison Formation at the LC site

The Forest Service offers tours of the canyon and track site. If you are interested contact the Forest Service Office at 1420 East 3rd, La Junta, CO 81050, 719-384-2181. If you plan to visit the area on your own, be aware of a couple of things. You cannot drive into the canyon without prior authorization. You can hike in on your own, but it is several miles in and out, and the summer temperatures can be brutal, so bring plenty of water and plan accordingly.

A large section of Dakota Formation slumping away from the main block provides a dramatic hiking experience

Lockley, M. G. 1991. Tracking Dinosaurs: A New Look at an Ancient World. Cambridge University Press, New York.

Schumacher, B. A., and G. A. Liggett. 2004. The dinosaurs of Picketwire Canyonlands, a glimpse into the Morrison Basin of southeastern Colorado. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 24(Supplement to 3):110A. (Poster page 1 and page 2).

Many other dinosaur facts can be found here at Boneblogger. Just search or select the category.