Isaac Newton famously wrote in 1676,“If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.” This gets to the heart of the scientific process—a gradual addition and refinement of human knowledge and understanding of the natural world. But, of course, sometimes even giants had wacky ideas.

The particular “giant” to whom I refer is Charles H. Sternberg, famed fossil collector. Sternberg began collecting fossils when he was seventeen, at a time when it was not exactly commonplace, in about 1867. And he dedicated his life to this unusual pastime, founding a family of fossil collectors when his sons continued the tradition for a second generation. Together, the Sternberg family collected a huge number of fossils for museums and science. There is hardly a major museum in the world that does not have one of their discoveries on display.

Sternberg started his career in the hills of western Kansas, collecting fossil plants from the Dakota Formation. He sent his specimens back to the young Smithsonian Institution, for which he received a letter of acknowledgment that he treasured his whole life. He was bitten by the “fossil bug.”

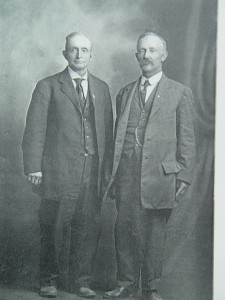

A rare photograph of Charles Sternberg (right) with his twin brother Edward (left).

By 1875, he enrolled in college where he studied briefly under Benjamin Mudge. Mudge organized a fossil collecting trip for 1876 to collect for O. C. Marsh, the Yale College paleontologist. Sternberg was too late to sign up with Mudge, and bitterly disappointed, and somewhat brazenly, he wrote a letter to Edward D. Cope, Marsh’s rival.

Sternberg wrote, “I put my soul into the letter I wrote him, for this was my last chance. I told him of my love for science, and of my earnest longing to enter the chalk of western Kansas and make a collection of its wonderful fossils, no matter what it might cost me in discomfort and danger. I said, however, that I was too poor to go at my own expense, and asked him to send me three hundred dollars to buy a team of ponies, a wagon, and a camp outfit, and to hire a cook and driver. I sent no recommendations from well-known men as to my honesty or executive ability, mentioning only my work in the Dakota Group.” (Sternberg 1909, pg 33).

Sternberg anxiously awaited a reply, and when he opened Cope’s letter, a draft for $300 fell out, a very significant sum. So began his professional fossil hunting career. Over the years he collected throughout the American and Canadian west. In the twilight of his career he semi-retired to San Diego, and was allowed to use the title of curator at the natural history museum.

Museums and libraries are marvelous places, full of fascinating treasures. It was while reading in the archive at Fort Hays State University’s Forsyth Library that I came across a carefully saved clipping of an article from the Los Angles Time Sunday Magazine from December 20, 1931, titled “The habits of dinosaurs,” written from an interview with the 80 year old fossil collector.

In the article, Sternberg is quoted as giving his vision of the life of some of the dinosaurs that he had collected over the many years. While I recognize that it is not really fair to judge the views of earlier experts, especially with the perspective of almost three quarters of a century of additional knowledge, but it can be damn funny.

Sternberg is quoted as authoritatively saying, “Dinosaurs were lizards. They stood and walked like lizards, not like elephants or rhinos. That is to say, the normal positions of their feet were outside the line of the body, just like the alligators of today, not inside or even with the line of the body, as are the feet of horses, elephants and other mammals. Moreover, the dinosaur, instead of standing up, on straight legs, as usually pictured, bent its legs outward, as do the lizards, and dragged it belly on the ground, again like the alligators, monitors and other large lizards of the present day.”

Dinosaur reconstructions of that period typically showed dinosaurs with spindly, lizard-like limbs, and tails dragging, but with a generally upright posture. Sternberg evidently did not agree, arguing in favor of his views with some odd reasoning.

Citing fossils of preserved dinosaur skin, he said, “Furthermore, the skin on the lower side of the abdomen of this dinosaur was much thinner and more delicate than on other parts of the body. This is further and strong argument for my claim that the dinosaur dragged its belly on the ground, as do the alligators of today, which so protect their vital parts from carnivorous animals…you may be sure that no tender-stomached dinosaur, whether it weighed forty tons or forty pounds, would voluntarily expose its tenderest and most vital parts to attacks by the tyrant dinosaur or any other carnivorous creature by walking erect.”

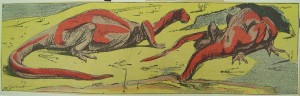

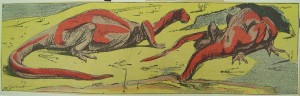

Illustration from Los Angles Times Sunday Magazine showing Sternberg's idea of dinosaur stance.

I totally agree. I hate walking around with my “tenderest” parts exposed. The accompanying illustration of Sternberg’s vision of the Mesozoic is hilarious, with giant sauropod (long-necked) dinosaurs hunkered down, presumably guarding soft spots. I am not really sure how Sternberg expected it would work for a forty ton animal to push itself along the ground with its legs sprawled out to the side, much less how it would support its own weight on its chest, but details, details.

Even though the article claims that Sternberg was a “man of facts and not fancies,” he was prone to exuberant musing about the prehistoric beasts he collected. While he could be wacky, we owe a great debt to the entire family for their contributions to science.

Further reading about the Sternberg family:

Everhart, M. Oceans of Kansas website, summary of the work of Charles H. Sternberg.

Everhart, M. J. 2005. Oceans of Kansas: A Natural History of the Western Interior Sea. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Liggett, G. A. 2001. Dinosaurus to Dung Beetles: Expeditions Through Time, Guide to the Sternberg Museum of Natural History. Sternberg Museum of Natural History, Hays, Kansas.

Rogers, K. 1991. The Sternberg Fossil Hunters: A Dinosaur Dynasty. Mountain Press Publishing Company, Missoula, Montana.

Sternberg, C. H. 1909. The Life of a Fossil Hunter.

Other interesting dinosaur facts are found here at Boneblogger. Search or select the category for more.

Sternberg, C. H. 1917. Hunting Dinosaurs in the Bad Lands of the Red Deer River Alberta, Canada. Charles H. Sternberg, San Diego.